The Softening of Christ

Over the course of the Renaissance, sculptural depictions of Christ proceeded to soften in appearance, rendering him increasingly more human. The process of this softening can be witnessed in Michelangelo’s works throughout the late fifteenth and early to mid-sixteenth centuries, and culminates in Giovan Caccini’s 1598 Christ as Savior. The philosophical and theological changes which occur throughout the late 1400s and the entirety of the 1500s were galvanized in the last decade of the fifteenth century, as may be observed in the debate between the millenarian Dominican friar Giralamo Savonarola and the optimistic Platonist Marsilio Ficino.

Savonarola, in the August of 1490, began preaching from the pulpit of the San Marco monastery. He preached about the end times, proclaiming that they were near; he believed that contemporary lifestyles signified the Apocalypse of Revelations. The lavishness with which Florentines, particularly those with high social status, lived their lives was to the Dominican friar utterly appalling. Savonarola was trained in Aristotelian and Thomist thought (Jurdjevic 62). Aristotelian thought advocated for a critical approach to doctrines; it demanded that one be wary of the establishment. Empiricism and deductive reasoning were the crux of this philosophy. Savonarola, too, was a devout subscriber to Thomism, which advocated both that the truth must be accepted regardless of origin, and that spiritual creatures are simple creatures. As such, the Dominican friar, whose purpose was to preach the Gospel and oppose heresy, was obligated to inform the constituents of his church about their sinful ways. In 1491, Savonarola rose to the position of prior in the San Marco monastery, and by 1493 had made his own order, separating himself from the Lombard Dominican Order. Seeing non-Christian values exhibited in the artwork of the time, Savonarola lashed out against the Medici for being patrons of what he considered pagan art. His words would eventually yield the exile of Pietro de’ Medici, for he was charismatic enough to rile the passions of the Florentines, galvanizing them into burning their collected artworks and expensive clothing in the public square, a protest against their own vanity.

Savonarola preached against the Humanist, inclusive philosophy that thrived during the Renaissance. He bellowed “that to be true Christians” Florentines must reject Platonist thought, which he saw as inherently pagan and contradictory to the Scripture (Jurdjevic 66). There were those, however, who believed otherwise. Marsilio Ficino fought for Platonist thought, despite being a member of the Church. Although Ficino himself was an ordained priest and a canon of the Florence Cathedral, he found that Platonic thought not only could be reconciled with Christian thought, but that within Plato’s works were the ultimate defense of Christianity (Celenza). He respected Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas, from whom Thomism is derived, and simultaneously Ficino found Plato to be a pre-Christ figure. Ficino argued that Christianity and religion needed to be founded upon philosophy, not merely the Scripture (Schumacher).

Though these two viewpoints may appear irreconcilable, it may be noted that the Valori, a noble Florentine family who rose to prominence during the absence of the Medici, held both as viable (Jurdjevic 70). Francesco Valori was a devout follower of Savonarola, but his son, Niccolò, believed in Ficino’s teachings. In fact, Niccolò wrote a biography of Lorenzo the Magnificent, not only to remark upon someone he believed was truly great and noble, but to defend Platonism, and to voice his opinion that there were sociopolitical benefits offered by it (Jurdjevic 73). To simultaneously vindicate the Medici and Platonism is to implicate Ficino’s message as the more valuable. The Medici were famous for many things, including their patronage of the arts. Lorenzo the Magnificent himself was the patron of brilliant artists, including Michelangelo and Leonardo, who sought to portray the beauty and passions of humanity. As Ficino saw beauty as a gateway to heavenly good, and the Medici sponsored so much beauty, it is easy to understand that by valuing one, Niccolò valued the other. In the 1490s, the Valori family, under Niccolò’s direction, were “collaborating more closely than ever” with Ficino, despite the fervor with which Savonarola had grasped Florence (Jurdjevic 70).

That a noble family would so openly reject the teachings of Savonarola implies that at the root of Renaissance thought was something not only inclusive in its nature, but radical and therefore unstoppable. Like a wildfire, Humanism had grown, bringing God down from the celestial pedestal upon which he had been placed in the years preceding the Renaissance. No longer was God solely to be found in the mouth of the Papacy; God could be found everywhere. Aristotelianism, and its derivative, Thomism, had led to an interesting position; if the truth must be accepted regardless of its origin, then it matters not if the truth can be found in Plato’s works or in Paul’s testimony. The truth is the truth, and must be respected as such. Savonarola’s teachings may have touched the hearts of Florentines for nearly a decade, but his execution in 1498 by the Church itself implies that his mode of thought had been forgone for something else. The stringent reign of a hard, aloof God was no longer acceptable to the people. The sixteenth century opened with a settled argument. Art was no longer seen as decadent nor unnecessary. Beauty was something to pursue, and as art portrayed beauty, art itself was necessary.

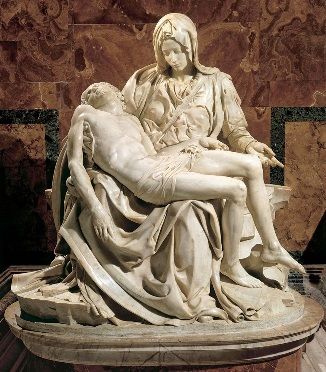

Michelangelo himself wrestled with this question over the course of his entire career. There are significant differences between the portrayal of Christ in the Pietàof 1499, the Risen Christ of 1521, and the Pietà crafted from 1547 to 1555. In each of these sculptures, Michelangelo softens his portrayal of Christ, rendering the Redeemer increasingly human each time.

The Christ of Michelangelo’s first Pietà is wasting away. His muscles atrophy beneath the flesh that the Virgin Mary grips so tightly. There is significant weight, for he is a corpse in the Virgin’s lap. His skin hangs slightly from beneath his knee, as there is no longer the resistance offered by a living leg. There is, however, no doubt in the viewer’s mind that this has been carved from marble. There is a rigidity and hardness that makes the fact irrefutable. Every ripple and curve of the work has been meticulously smoothed and polished, a skill for which Michelangelo was well-known. Despite the lifelessness Christ exhibits in this work, there is still an immutable majesty in his presence.

He looks not dead, but asleep, as if he has managed to gracefully fall into his mother’s lap, where she cradles him, almost as if he is a baby again. The way the light hits his form highlights Christ as the focus of the sculpture, though the woe of his mother is emphasized by the shadow cast across it. In this sculpture, we see Michelangelo’s attempt to galvanize sympathy from the audience. The Virgin Mary presents her deceased son to us, asking us to consider for whom Jesus was sacrificed. Her left hand asks us to see what has happened; she has lost her only son, the greatest man to ever live. The greatness of Christ is further illustrated by the form retained by his body. He was wounded, as is evidenced by the scar running along his side, and his sinew is wasting away, but otherwise he is in perfect form. The hair upon his head retains its lustrous curls, and his face rests in peace. This is not a humanized Christ; this is an immaculate, miraculous Christ.

In 1498, Savonarola is executed by public burning. He has antagonized the Church, ostracizing Pope Alexander VI and otherwise offending the Papacy by continuing to preach despite their contrary demands. By the time Savonarola was executed, he had become a howl in the wind. His rhetoric fell on ears immunized by the teachings and translations of Ficino, his rival. Ficino had been made president of the Platonic Academy in Florence sixty years before his death, in 1439 (Schumacher). In 1477, Ficino was ordained as a priest, and from then onwards his words were read and spoken throughout Florence. Ficino met with the Medici, who sponsored him in his pursuits during the reign of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Upon the death of Lorenzo and the Medici’s exile, he was adopted by the Valori, who too enjoyed his translations and teachings. Ficino had been working for years before Savonarola came to Florence, and the people were saturated with his knowledge. However charismatic Savonarola was – and the Burning of the Vanities that occurred at his behest proves the infectiousness of his ideas – Ficino had a firmer grip on Florentines. When it came time for the Florentines to consider whether or not to continue pursuing Savonarola’s methods or to maintain themselves as the center of the world, to continue the tracks laid by Humanism, they, perhaps because of decades of habit, perhaps because they had come to value themselves in a way Savonarola could never accommodate, elected to follow Ficino rather than Savonarola.

It may, however, have been that the people of Florence felt that Savonarola was pessimistic and didactic, whereas Ficino was optimistic, and would rather strive towards greatness than limit themselves to the spartan lifestyle Savonarola mandated (Boyle 719). Where Savonarola saw vanity and pagan thought and danger, Ficino saw aspirations and mirth and the precursors to Christian thought. The Neoplatonist believed that people naturally strove for goodness, and maintained the zeitgeist of the time in believing that one’s “bodily appearance indicated moral character” (Boyle 717). As such, if one were beautiful externally, in physique, then one was too beautiful internally, in spirit. Beauty, then, was vital to ensure virtuousness. And what sought to replicate and explicate beauty more than art itself? Were not forms and structures experimented on for the sake of finding the most beautiful? If art is an exploration of beauty, then art, regardless of subject matter, is necessary. It is good, or at least striving for goodness.

Still, the disruption caused by Savonarola’s rise to power in 1493 caused Michelangelo to depart Florence, to which he did not return until 1501 (Gietmann). Doubtlessly, Michelangelo was shaken by the tyrant, and it is argued that Savonarola’s words rang so fiercely in the sculptor’s ears that he lived with austerity the rest of his life (Gietmann). It is without wonder than Michelangelo’s next sculpture of Christ renders him softer and more languid. This Christ still maintains his majestic and muscular form, and there is regality in his gaze, but he has softened in that he no longer resists the reality afforded humans.

Here, Christ’s thighs are soft and round, not the hard and strained muscles they were in the Pietà. He strains to hold himself up, leaning upon his cross and staff. Originally, he was nude, referencing the first state of humanity in general; the staff, then, references the exile from Eden, in that humans were destined from that moment onwards to toil and travel rather than remain safe and sound within an eternal garden. That Jesus himself, after having risen, strains in the manner of humanity, and so implicitly references the human struggle, coerces one to believe that Michelangelo himself has changed in his perception of Christ. No longer is Christ merely a figure to praise and thank; Christ is, at least in part, a man. Of course, Christ must maintain his noble, holy stature, as Michelangelo was devoutly religious, but there has been a softening of Christ compared to the previous incarnation. Michelangelo had become wary of extremes, having been forced to flee the city he loved because of one man’s extreme religious views. A reflection of this arises with the knowledge that there was another Risen Christ which Michelangelo abandoned to create the one shown in Figure 2. The first attempt at the Risen Christ was meant to be seen from only one viewpoint primarily. The completed rendition, however, is in the round. That is, the work is a sculpture meant to be observed from all angles, from many vantages. Christ, and Christianity itself, is not meant to be viewed from solely one position, but from many. Christ may be found regardless of where one looks.

Thirty-four years later, Michelangelo works on one of his last projects. The rendition of Christ offered in this sculpture is one whose humanity bears down on him. Christ is dead, but he is not held up by remnants of his godliness; he is held up exclusively by his mother, his lover, and his friend. His weight is so immense here that his bones do not settle correctly. Instead, Christ’s leg appears to fall haphazardly to the ground, incapable of supporting his weight; his arm dangles at an unnatural angle, one that he would find incredibly uncomfortable were he alive. His arm and leg are twisted, broken versions of the grand limbs they used to be. There is no remnant of Jesus’ divinity in this Pietà. There is only the strength the other three characters are endowed with, and the presence of Christ. Thus, Michelangelo’s focus is no longer solely the power of Christ, as it was in 1499. The sculptor explores in his 1555 Pietà the relationships and connections built and maintained by Christ.

Whilst the virgin primarily holds Christ’s fallen body, Mary Magdalene holds his right leg, and Nicodemus – a self-portrait of Michelangelo’s – holds the three of them in his arms. Both Magdalene and the Virgin Mary are desolate, and Nicodemus himself holds concern, but his focus is not on Christ; Nicodemus, and thus Michelangelo, focuses on keeping the group together. He fixes his attention to the unity of the group, ensuring that they can manage, offering comfort. Death unites us all, the sculpture claims, regardless of background. The power of Christ comes from his ability to form relationships with all people and bring them together under one banner. No longer is Christianity divisive; Michelangelo argues through this sculpture that Christian love coalesces rather than dissembles.

Ficino, too, was known for restructuring religion to center about divine love rather than divine punishment. Ficino posited that joy was virtuous, as it was “the ultimate human passion” (Boyle 727). Without joy, one could not marvel at and therefore appreciate the gifts God bestowed upon humanity. Rather than align himself with the belief that laughter was either involuntary and thus a consequence of psychological impropriety or meant to rebuke someone for one’s stupidity, Ficino claimed that laughter signified pleasure and delight, and that it stemmed from “an expansion of spirit” (Boyle 722-723). He calls light the “laughter of the sky,” a definition laden heavily with Biblical associations. The first thing God made, according to the Bible, was light. To refer to light as laughter is to claim that laughter is not only natural; it is of utmost importance, and, furthermore, good.

This last aspect of Ficino’s teachings points us towards the eras beyond the Renaissance, towards Mannerism and its progeny, Baroque art. Mannerist works started playing with light in a way that the Renaissance could not have. With Renaissance art pursuing a naturalistic approach to imagery, striving to capture things as they were and reveling in the beauty of the world as it was, it could not have developed into a form in which light emanated not from beyond the painting. To do so would be paradoxical and hypocritical. Mannerist works, however, played with the placement of light within a work. Light could come from within a person, leading to works in which light emanated from one’s wrist or chest. The connotation of this in regards to Ficino’s conceptualization of light is that the people from whom light emanates are themselves innately good and beautiful. To be illuminated as Baroque subjects were, minimally but, through the low levels of light, rooted in a similar ideology. Those who are surrounded by light or who can shine in the darkness contain within them a beauty and grace that Ficino found to be comparable only to heavenly beauty and God-given grace. The beauty of God, then, was embedded in humanity, not solely the Scripture nor Christ.

Belief in the human aspect of God led to such works as Giovanni Caccini’s 1598 Christ as Savior. Caccini’s representation of Christ is incredibly soft. Christ the Savior is not regal, nor aloof; there is no sense of class-allotted pride in this sculpture.

The Christ of Caccini’s work embodies the quiet, contemplative, beautiful human Ficino strives to make of those who listen to his teachings. He is beautiful. Light appears to graciously fill his being. The cloth that drapes around his shoulders offers humility and modesty, rather than the brazen, naked style of Michelangelo’s Christs. Rather than marble, Caccini’s Christ seems comprised of faintly glowing flesh. Whilst Michelangelo’s works are obviously carved from marble, Caccini’s Christ seems to have had a smooth layer of marble gently pressed onto him. That is, Caccini’s Christ seems covered in marble, not made of it. Whilst the Risen Christ looks out upon his domain, the Savior Christ looks down and away, as if he is too humble to gaze into our eye, or too shy to see those who would offer him such praise as is worthy he who dies for our salvation. There is, however, as Ficino would have delighted to note, the hint of a smile, a promise of light and love and eternal grace.

Works Cited

Bacci, Mina. “CACCINI, Giovan Battista in ‘Dizionario Biografico.’” In "Dizionario Biografico", www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovan-battista-caccini_(Dizionario-Biografico)/.

Celenza, Christopher S. “Marsilio Ficino.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 2 Sept. 2017, plato.stanford.edu/entries/ficino/.

Gietmann, Gerhard. “Michelangelo Buonarroti.” CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Michelangelo Buonarroti, www.newadvent.org/cathen/03059b.htm.

“Gracious Laughter: Marsilio Ficino's Anthropology.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 52, no. 3, 1999, pp. 712–741., doi:10.2307/2901916.

Jurdjevic, Mark. “Prophets and Politicians: Marsilio Ficino, Savonarola and the Valori Family.” Past & Present, vol. 183, no. 1, Jan. 2004, pp. 41–77., doi:10.1093/past/183.1.41.

Kirsch, Johann Peter. “Girolamo Savonarola.” CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Girolamo Savonarola, www.newadvent.org/cathen/13490a.htm.

Nagel, Alexander. “Observations on Michelangelo's Late Pieta Drawings and Sculptures.” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, vol. 59, no. 4, 1996, pp. 548–572., doi:10.2307/1482891.

Schumacher, Matthew. “Marsilio Ficino.” CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Marsilio Ficino, www.newadvent.org/cathen/06067b.htm.